Could Saharan Dust be trapping Florida's humidity, making it worse?

Health concerns as Saharan dust set to return

Dr. Gayathri Kapoor, a pediatrician with Orlando Health, discusses health concerns for individuals with chronic respiratory conditions as Saharan dust returns to Central Florida.

ORLANDO, Fla. - Each summer, towering plumes of Saharan Dust cross the Atlantic, arriving in the skies over Florida and the Gulf Coast like clockwork.

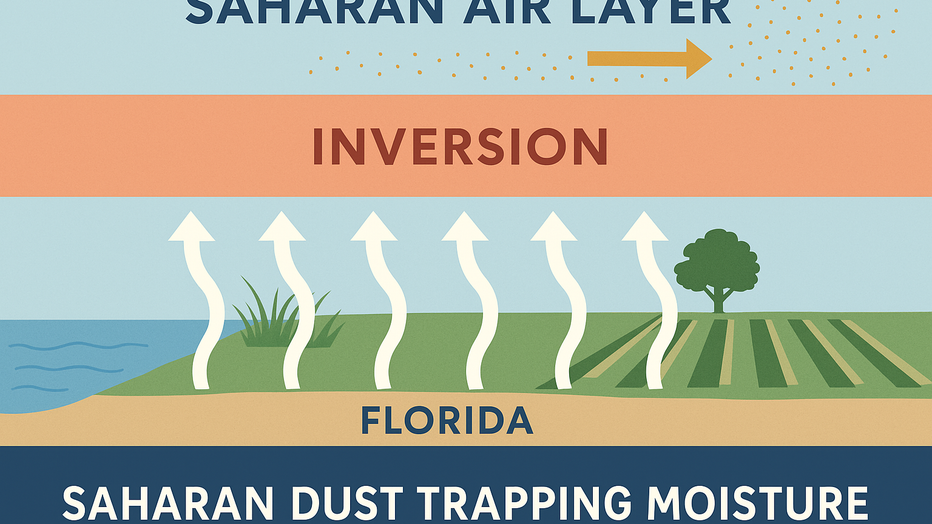

Known as the Saharan Air Layer (SAL), this vast cloud of dry, mineral-rich air is often linked to vivid sunsets, reduced tropical storm activity and sometimes even a scratchy throat. It's a dry and hot region of air existing mainly between 5,000-12,000 feet and, in this region, carries with it high above the ground properties of the Sahara: hot and super-dry.

Could the dry Saharan air make Florida’s humidity feel more unbearable?

What we know:

FOX 35 Storm Team Senior Meteorologist Brooks Garner hypothesizes that the dry Saharan air could ironically make Florida’s famous humidity feel even more unbearable.

Often it's the case, when Saharan air is present, it just feels hotter. While no conclusive research has been completed, there may be solid meteorological and thermodynamic logic — and a lot of personal anecdotal observation — suggesting that the SAL contributes to higher dew points than would be present in the absence of Saharan air, as it traps moisture near the surface. Today, dew points will range from the mid and upper 70s and may be measurably influenced by the presence of the SAL.

What's the science behind SAL?

Dig deeper:

The SAL is defined by a mid-level temperature inversion.

An inversion is a layer of warm, dry air that can exist above the planetary boundary layer, or "mixing layer," beginning around 1,500 feet at night, upwards of 8,000 feet by day. This warm pancake of air stops air below from rising above it and stops cooler and drier air high in the sky from mixing below it.

In short, the SAL tends to slow or stop the natural cooling and drying "mixing" process, which regulates our heat and humidity. This "cap" blocks surface-level moisture (and surface-based heat) from rising into the upper atmosphere, and that leaves behind dense, stuffy water vapor, unable to vent via convection to the upper reaches of the sky to be replaced with drier, cooler air aloft.

In Florida and along the Gulf Coast, where surface-based moisture is abundant — thanks to swamps, wetlands, agriculture, coastal waters and lush vegetation — this blocked vertical exchange means all that evaporated water has nowhere to go. This is especially noticeable late-night into late-morning, when the cooling sea breeze hasn't developed or moved inland. Water vapor pools under the inversion.

More on our surface moisture source

Every day, the sun’s intense rays bake the surface, prompting evaporation from oceans and inland water and "evapotranspiration" from plants and trees. (Plants do "sweat"). In a typical setup with active sea breezes and convective mixing, some of this moisture is lofted upward, diluted through the atmospheric column and eventually forms clouds and rain.

We see this just above every day in Florida's summer rainy season. But, under a SAL inversion, especially when surface winds are light and sea breeze circulation is weak or delayed, that moisture is effectively bottled up.

Dew points — a measure of atmospheric moisture — can skyrocket into the upper 70s and even low 80s (°F), levels typically reserved for tropical rainforests. It can feel like walking through soup, even in the absence of actual rain.

Saharan dust coming to Florida

Saharan dust is sweeping off the coast of Africa and will be working into Central Florida this week.

Why the Gulf Coast states may be uniquely vulnerable

Local perspective:

This potential SAL humidity trap may be more pronounced in the Gulf Coast states, especially Florida, for several reasons:

- Low latitude and high solar angle

The sun is stronger here, driving intense surface heating and evaporation.

- Moisture-rich environment

The landscape is a patchwork of wetlands, rivers, lakes and coastline — all sources of water vapor.

- Tendency for upper-level ridges (hot high pressure)

During SAL events, upper-level ridges often dominate, further suppressing vertical motion and amplifying heat.

When surface winds are weak — often the case under ridging patterns — there’s little mixing or air exchange to flush out the low-level moisture, so little venting. In this setup, the atmosphere becomes like a steamy greenhouse, capped by the SAL and cooked from below by Florida’s relentless sun.

When the daily sea breeze makes it into inland parts of Florida like Orlando, a welcoming dose of cooler and drier does finally add relief, but the steamiest feel happens under the SAL happens in the hours just before the afternoon sea breeze arrives.

While Garner says he hasn't dedicated the time needed to fully research and compare what "normal" dew point levels look like in locations like Orlando in summer versus those observed when the SAL exists overhead, he says circumstantially it does seem to trend toward measurably higher dew point levels.

The lack of formal academic studies on this topic invites further study! Are there any aspiring PhDs out there looking for a dissertation topic? Because this one’s just hanging in the air — literally.

Saharan dust coming to Florida

Saharan dust is sweeping off the coast of Africa and will be working into Central Florida this week.

STAY CONNECTED WITH FOX 35 ORLANDO:

- Download the FOX Local app for breaking news alerts, the latest news headlines

- Download the FOX 35 Storm Team Weather app for weather alerts & radar

- Sign up for FOX 35's daily newsletter for the latest morning headlines

- FOX Local: Stream FOX 35 newscasts, FOX 35 News+, Central Florida Eats on your smart TV

The Source: This story was written based on information shared by FOX 35 Storm Team Senior Meteorologist Brooks Garner and gathered from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Harvard University and the University of Miami.